In my last post, I talked about the lack of regulations in setting immigration bond and the great disparity in the amount of bond granted. A couple of weeks ago I had the chance to witness a few immigration bond hearings in San Francisco. Each hearing was different, and each had a different result.

The Immigration Judge granted bond in only one case, setting it at $10,000, and ordered only one release without bond. Both of these individuals had legal representation. The first one had been arrested for disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor. The second one was a Franco case, meaning that the individual was someone with a mental disability. In 2013, Franco-Gonzalez v. Holder resulted in an injunction requiring the government to appoint counsel and provide bond hearings for seriously mentally ill noncitizens detained in Arizona, California and Washington. This explains why, even though an interpreter was present, the judge did not question the man in a red jumpsuit sitting in court quietly and absent-mindedly. All questions and instructions were directed at his “qualified representative”, an attorney from a local non-profit organization who successfully argued that her client did not represent a danger to the community and that he would not be able to pay even the minimum amount of bond ($1,500).

The Immigration Judge granted bond in only one case, setting it at $10,000, and ordered only one release without bond. Both of these individuals had legal representation. The first one had been arrested for disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor. The second one was a Franco case, meaning that the individual was someone with a mental disability. In 2013, Franco-Gonzalez v. Holder resulted in an injunction requiring the government to appoint counsel and provide bond hearings for seriously mentally ill noncitizens detained in Arizona, California and Washington. This explains why, even though an interpreter was present, the judge did not question the man in a red jumpsuit sitting in court quietly and absent-mindedly. All questions and instructions were directed at his “qualified representative”, an attorney from a local non-profit organization who successfully argued that her client did not represent a danger to the community and that he would not be able to pay even the minimum amount of bond ($1,500).

I also witnessed several Rodriguez bond hearings, also known as custody determination hearings, for non-citizens who had been detained for six months or longer. For the first two Rodriguez bond cases, the attorneys simply asked for a continuance. To my surprise, the judge warned the two attorneys that in his experience, unless a stay (a temporary postponement of an order of removal) had been granted it would not be surprising if the non-citizens were removed before the next hearing. This is because in immigration court an appeal does not carry an automatic stay, nor does a Rodriguez bond hearing.

The other three individuals seeking Rodriguez bond were unrepresented and all appeared via video teleconferencing (VTC). The first one asked for more time to find an attorney. The next was a 26-year-old immigrant from Honduras who had been previously deported. He spoke English fluently and asked the judge to grant his release so he could go back to work as a cook and provide for his 3-year-old son and his family. The judge asked if he owned any property or had any savings; the young man replied that he only had $3,000. The judge denied bond, citing a “serious” flight risk because did not have family ties in the U.S. To be honest, I thought that if the judge was to deny bond it would be because in an effort to be honest, as this young man put it, he also said that he had been detained for a DUI previously and that ICE believed him to have had gang affiliation when he was a minor, which he vehemently denied. It seems that the judge did not think he was a danger, but still denied the bond despite the fact that this man’s whole family lives in the U.S., including his Legal Permanent Resident (LPR) mother, who had already filed a petition seeking permanent residence status for him as well.

The last hearing I sat through was for a homeless veteran, a legal permanent resident and former Marine. After being asked if he needed more time to find an attorney he told the judge he had written to several non-profits seeking legal representation but had not heard back from any of them. He told the judge he wanted to represent himself because he was having a “really hard time” being detained and wanted a chance to explain how he believed he is a citizen. He had taken a citizenship class and filed paperwork to become a citizen in 1991, while he was still on active duty. When the judge asked if he had any proof he replied that he had been homeless for the past six years and did not keep any documents. He also said he suffers from serious Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and was having a very difficult time coping with being detained. The judge denied bond.

After the hearings concluded I asked the judge about how lack of representation affects a case, and he insisted that it does not affect the ultimate outcome of bond hearings. But although I only sat through a handful of hearings, only two individuals were ordered released – one on bond and other with certain conditions – and both were represented. As I wrote in my last post, judges do not have to consider ability to pay, so I had to ask the judge about his reason for asking about the individual’s assets in one of the cases; he said that he did this in order to set bond at an amount that represents more than just a fraction of the individual’s assets and thus have stronger assurance that the individual will continue to appear in court.

Lastly, I asked about the effects of the Rodriguez ruling and whether more bonds were being granted now that more individuals were eligible for these hearings. The judge said that in his experience 99.9% of Rodriguez bonds were denied, as judges still had to decide whether the individual is a danger to the community or a flight risk. This is consistent with what I saw; not a single Rodriguez bond was granted that morning. However, this should not be interpreted as non-citizens being denied because they are an actual danger to the community.

Bond and Refugees:

If there is one group that has felt the harsh consequences of the lack of safeguards in immigration bond proceedings, including immigration bond, it is refugees, especially Central American mothers and children fleeing unimaginable violence in their home countries. After making a grueling journey though several countries, risking being raped, assaulted, and even killed, when they finally get to the border seeking asylum they are quickly detained and sent to “family” detention centers, such as Karnes, in South Texas. Karnes is run by the GEO Group, a private correctional detention company and was recently granted a temporary “residential child care license”, a move to circumvent an order from the Federal District Court for the Central District of California, which last August gave the Obama administration two months to release refugee children held in these unlicensed facilities. It is too soon to know the actual effect, but at the very least this means that the Obama administration can now continue to detain women and children indefinitely. Before last year’s Court order to release children from these detention facilities was issued, families had many complaints, including sexual abuse of women, lack of proper medical care for children, and bonds being set as high as $20,000.

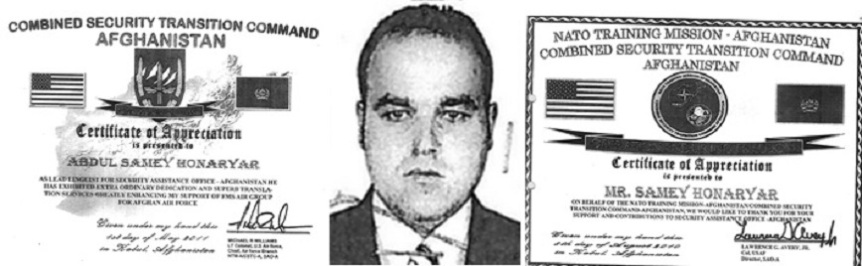

Samey, a former interpreter for the U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, who fled to seek asylum in the U.S. after being threatened by the Taliban has been detained for nearly a year. During Samey’s hearing before the judge, retired Lieutenant Colonel Mike Williams testified on his behalf and urged that Samey be granted asylum. Everyone thought that this was a “fairly open-and shut-case”; instead, the judge denied asylum and ordered Samey’s deportation. Samey did not have legal counsel. However, Samey was recently given a $25,000 bond, something he simply cannot afford. This high bond was set despite Samey not having a criminal record or presenting any danger to the community; he actually has family members who have been granted asylum on the same grounds, and even presented testimony by a former lieutenant colonel.

The Economic and Social Impact of Detention:

When a judge does grant bond, the person who pays the bond needs to have legal status, and in some cases has to be a family member. When immigrants cannot afford bond, it could lead to prolonged separation from their family and loss of social and economic support. The economic impact of detention could be measured in two ways – the cost incurred by the government when detaining immigrants for prolonged periods of time and the cost to the immigrants in the form of wages loss.

A survey of 562 immigrants detained in Southern California for six months or longer found that “approximately 90 percent were employed in the six months prior to detention.” The survey then calculated the collective lost wages due to detention to be nearly $11.9 million (or $43,357 per day). On the other hand, the government spent nearly $24.8 million dollars to detain these immigrants for an average of 274 days, with a daily cost of $161 dollars per detainee per day.

Sixty nine percent of the 562 surveyed immigrants had a U.S. Citizen or Legal Permanent resident spouse or child. About 94% were a source of financial or emotional support for their families, and 64% of these immigrants’ families had difficulty paying rent, mortgage or utility bills. In addition, 42% of families were unable to pay for necessary medical care and 37% could not pay for food. The lack of data makes it difficult to determine how many immigrants sitting in detention for prolonged periods of time are there simply because they cannot afford to post bond.

When bond is set at an amount a detainee and their family cannot afford, many are forced to contract with bond companies. Most companies require collateral, in the form of property or other assets, and they charge a non-refundable premium each year until the case is closed. This means non-citizens end up paying more than the actual bond amount and the collateral is not released until the end of the proceedings, which can take several years.

There is a new type of business that has emerged to service those who do not have property to use as collateral. The name of this company is “Libre” by Nexus. In my next post I will explain how “Libre” works and why customers are complaining.

You must be logged in to post a comment.